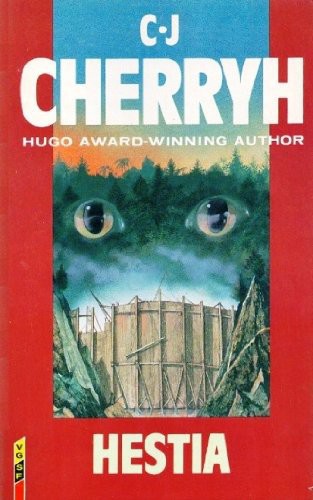

Книга: Hestia

The shuttle was visible through the rain-spattered glass, an alien shape in New Hope, towering sleek and silver among brown, unpainted buildings. It rested here only briefly: Adam Jones was in orbit about the world, a few days' interlude in her star-to-star voyaging, and the shuttle belonged to her, and to another existence, an alien dream in Hestia's sole brown-hued city.

Rain was the prime reality on Hestia: mist hazed distances and blurred the edges of middle-ground objects; rain pooled in the muddy streets and dripped and sweated from decaying buildings; gray monotones of cloud and brown of earth and flood persisted, while the colony died.

In the streets a thin shout went up. A group of revelers snaked by, arms linked, weaving and slipping in the mud, ignoring the drizzle. It was festival; a ship was in port. They paused, lifted a bottle in drunken salute, shouted something and wove away, linked, drab brown-clad folk quickly lost in the rain-haze and the maze of their ramshackle buildings.

Sam Merritt let the homespun curtain fall across the depressing sight and paced back to his chair, where papers were scattered on the scarred table. This unpainted room with the creaking wooden flooring was all that Hestia afforded of governmental splendor, New Hope's official residence, its best hospitality; and Merritt cast a regretful glance at his baggage still sitting unpacked, a forlorn cluster of black cases in the center of the floor.

A door opened and banged shut downstairs; footsteps creaked heavily up the treads. Merritt let himself down onto the hard chair by the table and leaned against the edge, gave a casual glance as the door opened and Don Hathaway slouched in, rain-damp and grim. Hathaway brushed droplets from his jacket and wiped his hair back, sank down on a corner of the nearer bed, shoulders sagging. He was older than Merritt's twenty-eight years, gray-templed. His face was growing heavy and habitually sullen, and the lines had deepened since their landing.

"Been out in the town," Hathaway said.

Merritt nodded. That bleak look did not invite comment.

"Sam," Hathaway said, "when we touched down and had a look about, I kept telling myself it had to be better somewhere… in town, out-country, somewhere. But the governor's briefing this morning—" He gestured loosely at the table, the scattered papers. "It's finished, Sam."

"What do you mean?"

"I talked to Al a few minutes ago, out in the town. And when that shuttle lifts, we're going to be on her."

Merritt looked at him, swallowed, shook his head: no refusal, but an echo of Hathaway's despair. His heart was beating hard. "Seven years of traveling to get here, Don—for turning around again—"

"And maybe we'll live to see home again." Hathaway wiped at his graying hair and rose, walked to the bedside table where a bottle sat, gathered up the dirty glasses with it and brought them to the big table, set them down and poured. He sat down then and pushed one across to Merritt. "Been out in the town. Seen it. Seen enough, Sam. Mud and farmers and things falling apart. And the mentality of these people—look at this place. Falling down, and not a hand turned to clean it, let alone fix it. Saw a man sitting out there in the rain, just sitting, drunk and staring at the water. Saw machinery patched with wooden parts, to work by hand. Windows patched with wood and paper. A boy tried to knife one of the crew last night, did you hear that?"

"Drunk, probably."

"Tried to rob him."

"These people begged for help fifty years ago, Don. They're destitute. Is it their fault?"

"Well, it's no fault of ours, either. We don't have to spend a year of our lives paying for it."

"The government is paying us plenty. Think of that. Add that up, what it'll mean to us."

"The agreement said—" Hathaway jabbed a finger at his palm "—that we were to come out here and look over the situation first-hand, to see if we could work out a system to control the floods… or to see if the world has the resources left to handle the problem at all. If it has the resources left. I've made my determination on that score. If you agree and go along—"

"Pull out without even looking at the upper valley? Don, we owe them at least that much."

"The ship's calling the shuttle up and she won't wait. You know what's involved, to throw a starship off-schedule."

"So for the sake of a year's wait on the next ship, you're going to throw this colony and a good slice of our own lives—"

"Sam, Sam, if I thought it would do any possible good. I'd go up there and look at that valley til the sun froze. But listen: listen to me. Even the original survey said this valley wasn't right for permanent settlement. And what did these people do? They ignored that instruction and built homes here. It's their own stupid choice. Another point: equipment. It's beyond recovery, flooded out, lost, cannibalized, broken, whatever. Our contract runs five years on-world at most. What could we do here in that time? Nothing. Nothing that could make any difference. They'd be needing other engineers to replace us and that could take decades, while all we've done goes sliding into the mud and bureaucrats dawdle. Hestia isn't going to live through another long wait. No. Someone's got to make the decision and get these people off this world or out of that valley, and that's not our field. I say we recommend removal, emergency basis, and leave nothing in the hands of the bureaucrats. So we take our million for riding out here to look; and we split it and go to the next prosperous world and retire. It's best, even for the Hestians. No need to be ashamed of that. It's crueler the other way."

Merritt shook his head, looked at the room, at Hathaway. "They'll not go easy. A year, one year… just the effort, even a useless one… don't you think they'd accept the decision to abandon the colony a lot more readily if they knew we'd seen the situation ourselves, if they knew we'd tried?"

"Sam, I'm forty years old. By the time I get somewhere else I'll be closer to fifty. I came out here maybe to settle down and practice my profession; but it's hopeless. There's nothing here. I'm getting out of this now, while it's quiet, before these drunken farmers have the chance to realize what the score is. Selfish—maybe. But so far as I'm concerned I've fulfilled that contract and I've nothing to be ashamed of. I came, where most wouldn't; and I took the chance and I've seen what I want to see, and all I want to see, ever. I'm not going to waste the rest of my life on this."

"Does Al…" Merritt asked finally, "does Al feel the same way?"

"Yes. Look, you'll get somewhere worth living for when you're thirty-six, thirty-seven, something like that. You'll have time to start over and enjoy that half million. Right now maybe you've got leisure for mistakes, or think you have. Don't think I don't understand how you feel. I was seven years younger when I started out on this crazy project—but seven years more will change your perspective plenty. You owe yourself better than Hestia has to give."

"Give it a year."

Hathaway frowned and looked at the floor and up again. "I've been too long on Adam Jones to want to change ships for so little advantage to anyone. All right, I'll admit it: I want the comfort of people I know around me. I want my friends. I want the place I'm used to. I gave Hestia most of my young life. I'm not going to throw the rest of it away on a lost cause. I'm going out on the ship that brought us."

"Isn't it maybe something you decided… even before you saw the world?"

"Sam—I resent that."

"Isn't it the truth, after all? Now you've talked Al into agreeing with you. You'll get him to sign that removal, and all you need is me."

"Look, every year we put these people off with false hopes more of them are going to die in the long run. That's no kindness. You know if we don't stay, if we've left a marker aloft with that order, these folk will be taken out with the next ship; and that's the best thing we could do for them."

"The colonists won't go. They'll fight at having it done this way. They've proven that. Adam Jones tried to take them off once before; other ships have likely tried. They won't. You and Al and I, we could prove to them it's best."

"We can prove it by leaving. They'll fold, when they're facing reality, when they have to realize there's going to be no help from Earth. And so what if they're willing to fight over the question? Does that give us equipment or help us stop the rain?"

"It's not right."

"It's not as if the whole colonial program depended on Hestia any longer. They—"

"Aren't important."

"Sam, they were supposed to have gone from phase one to industry fifty years ago, but they're going steadily downhill. They're without machines or power. Most of the last generation hasn't learned to read."

"So we take them off Hestia and drop them into a culture they can't hope to understand."

"Or let them starve here. Sam, they knew, they knew this was coming. They knew from the start the valley would flood whenever the weather rolled around to one of its long wet cycles; they were to use the valley and then move out of it; but no, they didn't believe geosurvey; they've been sitting here a hundred years absorbing what they were given in the way of aid; and now they want us to build them their dams so they can go on sitting and vegetating."

"The floods got them before they had a chance. What could they do once they'd lost their machines and their momentum? They've survived. They've done that for themselves."

"Don't tell me they've tried. Look at New Hope. This rotting mansion is the only building in all the town that was really built as a residence, and it was the old colony dormitory. The rest of the buildings were all warehouses—or are to this day; and not a building in the whole town is younger than a hundred years. They haven't touched this place, they haven't done anything or built anything together since the day they were founded. They chose their little plots of land upriver, gave up any concern for government or for the colony's future. They just let all cooperative projects go until it was just too late.

They don't even have electricity, for pity's sake. Now the farmland's gone, silted into the bay so they can't use that either; and they're breeding insects and disease out there in the summers in that lagoon. They die of diseases nowhere else has heard of. Adam Jones will put us all through decontamination or risk carrying plague from here to Pele."

"With drainage, dams, power production—"

"Ah, Sam, they'll do that when they fly unaided. No. I've ordered my baggage back to the ship and so has Al. Want yours moved with it—or do you want to go it alone?"

Merritt stared elsewhere, at the windows, at the steady drip of rain. Thin shouts drifted up from outside.

"That's how it is," said Hathaway. "If you won't sign the removal, it won't go through; we'll lose the money. Al—gets his. His contract is prepaid. All you can do is hold me from mine. From any future. From all I have left. You want to do that?"

Merritt shook his head. "If you and Al are going, there's no arguing, is there? If you'll go without the money—there's no way. All right. I'll sign your paper."

"Crew's going to assist. They'll carry in some meaningless crates, get our luggage out again. When people here find out—"

The downstairs door opened and closed. Hathaway put himself on his feet. Merritt did likewise, went to the window and looked out anxiously; there was no one. Single footsteps sounded on the board stairs, light and quick, and reached the door.

It opened. Lilith Courtenay slipped inside with a lithe move and shut it quickly—silver-suited and glistening with rain, a glimpse of elsewhere in the drab room. She shook back her hood, looked about with a grimace and a look of disbelief. Adam Jones was stitched on her sleeve, and the emblems of worlds and stars years removed from Hestia: crew, and disdainful of the worlds the patches signified, a breed apart from groundlings.

"I wouldn't have expected you," Merritt said. His pulse was still racing from a moment's guilty fright. And suddenly he was embarrassed, ashamed to be found here, by her, in this shabbiness. She shrugged her silver shoulders.

"Why, could we stay apart from carnival, love? All the drunken farmers? Don't you hear them in the streets? All New Hope's at the port celebrating, and so are we." Her face went sober. "Al told me the news. You're recovering your sense."

"News travels too fast. Who else knows?"

"I had it from Al. He's aboard."

"I'd better stray out in that direction too," said Hathaway. "Sam you wait a bit and then you take a casual walk and head for the field too. No baggage. We'll get it if we can. If they get onto us—it could be ugly."

"I'd think so," Merritt agreed, and watched sourly as Hathaway left.

Lilith Courtenay shrugged, hands on hips, walked round the table to put her hand on Merrill's arm. She looked up, pressed his elbow. "Sam, I'm glad, I'm glad you've come to your senses, even if it took you seven long years to do it Didn't we always tell you what you'd find on Hestia? We tried to warn you."

"Don's found the excuse he was looking for, at least."

Her dark eyes went troubled. "But you agree with him. You understand how it is here. You are going to leave."

"I suppose I am."

"You don't understand these people. They wouldn't be grateful if you tried and failed. They'd likely turn on you and kill you. They're like that. And some of us would miss you if you stayed behind. I would. I would. We've been together for seven years."

"No ties, Lil, you always said it."

"It'll be fourteen years before I see Hestia again. If you'd stayed out that five-year contract and gone elsewhere, I'd miss you that round and we'd be near fifty before we had a chance of meeting again. You were a transient. I'm crew. We stay to our own. But that could change. If you were family—"

"That's all right for you, Lil, but I'm not sure it's right for me. You were born to the ship, four or five generations of that kind of life. I'm different. I'm Earthborn."

She laughed soundlessly, a crinkling of the eyes. "Well, part of me is Adam; but my mother scattered her affections from Sol to Centauri and back again, and I've never been curious enough to backcount and know. So maybe we have Earth in common, who knows? Would you trade your life for Hestia?"

"I can't think of it clearly. I'm being pushed. I can't make you any promises."

"Can't you? But I don't think I ever asked for any." She gestured toward the windows. "It's a celebration tonight, the end of festival. Adam's people are out there, performing another of our many services—seeing that gene pools don't go inbred, you know. And nine months from now there'll be new Hestians, cruel as it is. Carnival is every year for a colonist, years between for us; but this time I've no interest in it. I want you back. You know I wanted your children before we had to split up. I really did. I couldn't imagine letting my first be someone else's. You wouldn't have it. Now—it's different, it's going to be different."

"You could always have chosen to stay with me on Hestia. I waited for that."

She gave a palpable shudder, shook her head. "Some things are too much to ask."

"Poor gypsy. You don't know what it is to call any place home."

"Adam is home. Come back to it. We don't love groundlings and we don't love passengers. Come back. Stay. It can be different now."

He nodded slowly. "All right. All right, Lil. You've won. I'm coming. Get out of here, get yourself back to the port. I think it's better you go first and get aboard. It'll be dark in a while. I'll take a walk in that direction toward dusk."

"No. Come now."

"We'd attract attention. Better separately."

"I'm afraid, Sam. I'm afraid of these people."

"Then be careful; and I'll be." He touched her face, kissed her with the casual affection of long acquaintance— it was different; the touch lingered; and guilt and wanting were mixed in him, a knot in his stomach. He took her by the arm and turned her for the door. "Go on. Go on, get out of here. The longer you stay, the longer it takes us both getting to the ship. I'll be after you when I know you've had time to get there."

It was raining again, pelting down in torrents as Hestia's sun slipped from gray day to murky evening. Merritt drew back the curtain and checked the street, found it vacant, nothing but trampled clay and rain-pocked puddles. There was no sound but the fall of water.

He put on his jacket and zipped it up to the chin, stuffed the pockets with personal articles he most treasured, checked the luggage for any item he would miss, and closed it, hoping that the crew would manage to get it aboard all the same, and in a different mind, inclined to beg them not to try, not to risk any hurt to local folk or crew in an argument. He had enough weight on him without that.

The downstairs door slammed open. Steps thundered up, in multitude. Crew, he thought, anxious for having delayed too long; and then the door opened, and he knew otherwise.

Hestians. Half a dozen of them, brown-clad and bearing the armband of the local police.

"Were you going somewhere, Mr. Merrill?"

Merritt stood still, remembered his hand in his pocket and took it out very slowly. He had no weapon. They had sidearms, and truncheons.

"Something I can do for you?" he asked them, hoping that they would still have some reluctance to offend life-giving Mother Earth.

"Governor wants you," said the officer in charge. "Now."

Merritt considered the proposition, the lot of them, the scant chance of dashing through armed police and through a hostile town. There would be crew still outside, the chance of a riot. He reckoned Lilith Courtenay at the ship, waiting; and that waiting would grow impatient, would produce inquiries and action. He trusted so, desperately.

He shrugged, showed empty hands, and went with them.

Governor Lee was a stout, balding man of gentle manner; a man perpetually worried, seeming distracted… no figure to inspire fear. Merritt had met with him, reckoned him and catalogued him; and those calculations were in shambles. Lee stared him up and down with that same worried air while the police lined the room and guarded the door and Merritt felt very much alone in that moment.

Lee had no reputation, no authority. The briefing Adam had given indicated twenty years of idleness, twenty years of starship contacts, meetings with disdain on the part of crew and abject anxiety on the part of Lee. There were, in fact, few people accessible for Lee to govern, and he relied desperately on the starship supplies and Earth's charity. But of a sudden the man moved, when all had assured him otherwise, and that fact alone removed any certainty from the situation. Merritt folded his hands in front of him and made no protests; none seemed profitable. "Sit down, sit down," Lee said.

Merritt did so, stared at Lee across the width of the desk, met those wrinkle-shrouded eyes and tried not to break that contact.

"You were running, Mr. Merritt." Merritt said nothing.

"Well," said Lee, "I saw it in your faces the day you landed; and this afternoon—I knew I hadn't won them, but I'd hoped I'd won you, Mr. Merritt."

"I was going out to see the town. That's all. Your police—"

"Please, Mr. Merritt. You were leaving. We know where the others are. A man is dead, finding that out. It's much easier if we're honest with each other."

"We thought—" The words came out with difficulty. "We thought if we drew back we could talk with you, that you'd believe us then and move out. Governor, you admitted yourself that there's no equipment. Nothing. What do you expect of us?"

"Advice, Mr. Merritt. Professional skill. You tell us how and we do the work."

"A colony of five thousand, with no machinery and no manpower to spare. And if you make a mistake, Governor, you'll not get anything. Take my professional advice. Get out of the valley. Better yet, get off Hestia while you can."

"We've asked for weapons, for metal for machinery, and fuel to run it; we've asked for sensors like the equipment you have so we can protect ourselves in the highlands. But we don't get these things. We can't handle them; that's the word we get. It would take the diversion of a starship for several years to support that kind of expedition, and five thousand human lives aren't worth that kind of money, are they? We've never had a chance, and they won't jeopardize the finances of the bureau to save Hestia. No, it all comes down to budget. It always does. You prolong your agony, Mr. Merritt. That's all your help does."

"Sir—"

The governor's tired eyes focused on his, held. "You three cared enough to come. What happened? Wasn't the money enough to buy you out?"

"Why won't you give up this colony? Why won't you listen?"

"Can't another groundling understand, Mr. Merritt? This is home. It's that simple. And someday the rains will stop again. But it's precious little we have to hold to, with our fields underwater during both growing seasons and no water in winters and fevers in summer."

"You don't have to leave Hestia. The highlands hold what you need. If you'd listened to survey—"

"The highlands also have other inhabitants, Mr. Merritt."

Merritt folded his arms and stared at the floor and elsewhere.

"You don't believe."

Merritt shrugged, met Lee's eyes coldly. "Men have always seen ghosts. Maybe they follow us. No, sir. I've heard about them. But survey turned up nothing."

"They're real, Mr. Merritt. And there are more of them than of us. They leave their tracks around our farms, they kill our livestock, sometimes break fences or set fires. Sometimes they kill, when we're careless. They're real; and you won't give us weapons and you won't give us sensors. So we stay in the valley. They've given that over to us, and we'll go on holding it while the human race lasts on Hestia. You three were our last real hope; and since you've decided as you have—what do we have left?"

"I'm sorry, sir. But I don't see there's a choice."

"I don't see I have one either. No. No, Mr. Merritt. For once the opportunity belongs to us. I have you here in the town, and I don't think Adam Jones is going to do anything about it. If they won't throw a starship off schedule to save five thousand lives, I don't think they'll do it for one man, do you? You're a victim of the same kind of logic as we are, Mr. Merritt. I'm very sorry. I certainly don't want to do you any harm, but consider my motives. Five thousand lives against the comfort of one: again the logic of numbers."

"Adam Jones will leave a marker, and then where will you be? No starship will touch here."

"But we'll have our engineer."

"I can't work alone, sir."

"I wish they hadn't deserted you; I wish they'd been willing to stay; I wish this weren't necessary at all. But that marker beacon might be left whether or not we let you go, mightn't it? And we'd have nothing. We'd die here. We're sorry, Mr. Merritt. The move is made. There's no going back from it."

Merritt let go a long breath, leaned back in the chair, considering Lee, the men about him. "I don't like being pushed. Whatever your feelings, I don't like being pushed. I recognize my choices are limited… but I still have them."

"Yes."

"I'll make a deal with you then, and keep it."

"What sort of deal, Mr. Merritt?"

"You need my cooperation and I want off Hestia. So in work at this project for a year, and work at it with the best of my ability, so long as you provide me help. But when that next ship comes, I'll leave on it unless I've been able to find some solution to your problem."

"Your contract specified five years."

"One."

"After the ship leaves, there's really very little reason to have a bargain, is there? If we don't allow it, there's no way you can get near that next ship. You'll live here, with us, as we live. If we don't get that dam built, Mr. Merritt, you stay. That's the last and only threat I'll make to you."

"What am I supposed to use for equipment? What I have is on the shuttle."

"Then send for it"

"It won't be enough, even that. You understand that."

Lee made a small and inconsequential gesture. "That's between you and your friends. Ask them. We'll arrange the contact."

"We have alternatives," Don Hathaway's voice said. "Put us through to the governor. We'll make them clear."

"I think they already are," Merritt answered. Static spat. The mansion's communications center, solar-powered, was a patchwork collection of outmoded equipment that must be dusted off once yearly to use with the starships and the shuttles. "Listen to me. We're going to have people dead if you make a move in this direction, and I don't want that. Besides, it's trouble for Adam. The Colonial Bureau wouldn't understand a firefight between a starship and her colony. These people are desperate and they'll fight. So just set the gear and the supplies outside the ship. No argument. Please."

"Don't be a martyr, Sam. Give me a sign if you're not talking with a gun to your head."

The guard officer moved, interposed his hand; Merritt held his free of the equipment, made a slight gesture and received permission.

"It's free will, Don. Believe it, sure as we met on station shuttle."

"That's a true sign. All right."

"Wish you were here with me. I could use the help. But that's asking too much, isn't it?"

A silence. "Yes," Hathaway said finally.

"Thought so," Merritt said. His voice felt hollow; the heart of him did. He held a curious lack of bitterness. "Is Lil there?"

"I'm here, Sam."

"Same invitation, Lil. I could use the company."

There was a long pause. "I can't," she said finally, miserably.

"I figured that too. No hard feelings."

"I'm sorry, Sam."

It was incredible; it sounded as if she were crying, and that was not at all her habit.

"Goodbye," she said.

The contact went dead.

It was misting rain again, the sky over New Hope its usual unappealing gray, the waters colorless from the floating dock to the lagoon to the sky. Merritt descended the wooden steps to the floating dock and paused to turn his hood up against the chill wind that blew here in the open, drenching him.

He had wondered, when they had promised him a boat upriver, just what transportation Hestia could offer. There rode the answer: Celestine, broad-bottomed and rearing a tall smokestack amidship. A wheelhouse took up much of the available deck, and the rest of the space was stacked with cordwood and crates of what Merritt took to be his own gear. Often patched and now much in want of another painting, Celestine seemed easily half a century old, half as old at least as Hestia.

Merritt looked back, where the governor's police lined the shore, with townsfolk to back them. It was superfluous. The shuttle was gone from the field; Adam was gone, the long silence fallen again about Hestia. He shrugged, turned, feeling their collective eyes on his back, and walked the heaving surface to the gangplank, a treacherous bit of board suspended between the moving dock and pitching boat. He made it with a slight stagger, caught his balance again on deck.

A gray-haired man leaned against the wheelhouse, watching him—made no move of welcome, hands in the pockets of his patched coat, unshaven jaw slowly working over a toothpick.

"Amos Selby?" Merritt asked, when the man seemed disposed to stare at him indefinitely.

The Hestian bestirred himself, drew a hand from his pocket and offered it with no show of welcome. "You'll be Mr. Merritt, to be sure. Your gear's all aboard."

"Where shall I stay?"

Selby gave a quirk of the mouth that might have been humor. "Well, you'll stay where you can find sitting room, Mr. Merritt. Go where you like. We got one deck, got no police here, just water, all around."

There was disturbance on the dock. Footsteps echoed across the wooden planks at high speed; a youth raced down the steps and across the floating landing. Amos grunted.

"My boy," he explained. "Come on, son, hurry it up."

The youth leaped the gap and swept the cap off his blond hair, put it on again straight, and stood staring at Merritt. He was about twenty, almost delicate, and fairer than his father ever could have been. Merritt thought of the star-ships and the yearly carnival at New Hope, and wondered.

"Sam Merritt—Mr. Merritt—my boy Jim. Get to work, Jim. We got to get moving sometime today, you know."

"Yes, sir," said Jim, looking contrite, and moved off to take charge of the engine. Amos shook his head and wandered off to the wheelhouse that was four steps up a wooden ladder.

The engine was slowly coaxed to life, a hissing, sluggish museum piece. Merritt walked back to see it work, and Jim looked up at him with a shy grin, but the noise was too much for talking. Jim shouted orders ashore; a pair of men cast them free and the engine began to labor, with Jim running here and there to pull in the cable. Celestine slewed out into the current and Merritt walked back to watch the spreading wake, white curl on brown, rain-pocked water, and to stare at the shore. The men became only silhouettes beside a sprawl of brown buildings. The shore dwindled, and the water spread equally on both sides, with sand and grass along the banks.

He walked forward then, to the bow, stared out ahead at the countryside and the river, the land flat and flooded and obscured by misting water. The wind cut through the jacket. He shivered finally and threaded his way back to the wheelhouse, climbed the steps to that scant shelter, where Amos plied the wheel. The structure was open, affording view, letting the wind whip down and up and out again.

"It's freezing," Merritt said, teeth clenched.

"Does get a little cold," Amos agreed.

"Do you travel this course in winter too?"

"No way anything moves on Hestia otherwise. Boat's got to come and go."

"How many other boats are there?"

"Five."

"I'm told you know the river best."

"Have to." Amos took the toothpick out of his mouth and pocketed it, as if he had finally made up his mind to converse. "I'm supposed to take you as far as Burns' Station and stay with you. I hear you're supposed to save Hestia."

Merritt sank down on the worn counter that rimmed the side of the wheelhouse, where there was some scant shelter to be had. "I get the impression, Mr. Selby, that you don't think much of the business."

"You're the first Earthman in a hundred years to set foot on Hestia and I bear you don't like it much. Myself, I don't trust offworlders much. I don't figure we ever got much from outside."

"I don't figure we ever got much from Hestia, for all that was put into it."

Amos Selby nodded slightly. "True, no denying it, Mr. Merritt But you never needed nothing we could give. So here you are. I suppose we're supposed to owe you something on that account, aren't we?"

Merritt refused to rise to the argument. There seemed no profit in it

"Well," Amos said finally, "my advice is free for the asking if you have sense enough to want it." He reached for the whistle and blew it sharply, indicated off to port as Merritt stood up to see. A house stood on a hill, tree-rimmed, out of the reach of the river. "James' place there," Amos said. "Used to be a dock there. Nicest place on the river, closest to the city. Dock washed away this fall. They haven't got it rebuilt."

"Do you make regular stops on this run?"

"Not this trip. You're my only cargo. But usually, yes. Some regular, some when I'm flagged in. Everywhere a group of farms can give me a dock. If it wasn't for us rivermen, there'd be no Hestia at all. Many's the time I've had to bring Celestine in close to get a family off the porch or had the deck full of sheep and pigs when someone's field's been washed over. We're a stubborn breed, but there's none of us yet learned to breathe water."

Jim brought up tea and sandwiches about noon, into the wheelhouse, the walls of which were cluttered with Merritt's tablets and the corner with a plastic book of charts. Amos slipped a loop on the wheel and kept an eye forward while he ate, pausing to correct course now and again, and now and again to stare at Merrill.

"How old are those?" he asked Merritt finally.

"They're the original survey charts. They're what they gave me to work with."

"You mean the survey a hundred years back?"

"From what you've said and from what I see, I can tell something of the extent of the changes. It's bad. It's a lot worse even than was reported."

Amos washed down a bite of sandwich. "You'll find out more than that. I don't read much: you'll guess that. But I know this valley and this river, and I can show you plenty, how it was and how it is. I can tell you most every sandbar and shift of current from here to Burns' Station."

"And beyond that?"

"No, sir. No one goes up there, and no one will take you there."

"Not for any amount of asking, then?"

"No. No, sir. First of all you'd need to pass white water against the current and there's no boat could do it. And then you're into uncharted river and wild country if you made it. No, I'll do whatever errand-running you want done from the Station to New Hope and points between, but I value my boat and my own neck too much to run beyond the Station. I don't know that I'll convince you of it too early, but there's times you'll be safest just to take advice untried."

"Is the river open year-round between the Station and New Hope?"

"Mostly." Amos waved his cup toward the view. "Shell drop considerable after the fall rains quit. Then there's sandbars where we're riding now high and easy. Come spring when the ice melts in the high country, there'll be pigs swept clear to sea. Then summers, there's seldom any rain and it's sticky hot. The killer floods, those are the ones in spring, the sudden risings. If a man tries to gamble and stay on his land when it's a question of a few feet of crest between him and drowning, well, we lose some few each year that try to outguess the river."

Merritt looked out, braving the wind. The river was very broad at that point, isolating dead trees and small hummocks of earth, fence posts and bits of field, and houses which had ceased to be habitable. Newer homes could be seen occasionally against the backdrop of rougher highlands on either side of the river, fields terraced on the hills. In the north a ragged line of mountains showed as a gray horizon, bristling with trees.

"Is that the Upriver you're so afraid of?" Merritt asked.

"Yonder? Part of it. That's Williams' Heights there, just big forest. Myself, I don't trust any forest, but there's some with the nerve to bed down next to it. Trouble is, it runs on and on forever, right into the Upriver itself, and what lives in the Upriver can live there too, for all you know. I don't like places like that at all; no one does; but there's not so much land left now that folks can be choosy. Some even get brave enough to cut a few trees into the deep forest and clear them new land."

"What's to stop them?"

Amos gave him one of those guarded looks and bit thoughtfully at the sandwich, swallowed again. "Well, Mr. Merritt, it's just well known on Hestia there's things in the forest that don't like axes; and some of them are downright clever about showing it. Little trees nobody misses; but you cut down a big one, now, a really old one, well, your fences could fall down or your livestock could die or your house could catch fire."

"Truth?"

"Truth. And another truth, friend—when you start building your dam up at Burns' Station and backing a lake up into the Upriver, you're going to flush a few things out of there that none of us are going to want for neighbors. But the lake has to be. We'll solve the other problem when it meets us on our own grounds."

"Maybe the dam shouldn't be built there. Maybe it would be better to create several smaller reservoirs up-river."

"Huh. You'll get Hestians into the Upriver when rain falls up."

"Because you're convinced something lives there. But you tell me then, Mr. Selby, how a group of minded beings could have been missed in the first survey and then live next to a human colony for a hundred years without leaving something in the way of tangible evidence they exist."

"We got plenty of evidence. Dead men and livestock."

"Animals could do that. It doesn't take sapients."

"Didn't claim they was human. But clever and mean, yes. Friend, you're in the middle of civilization right now. When you've lived next to an Upriver woods for a month or so, you'll believe in a lot of things." He galvanized himself into sudden action, put down the food and took the wheel, for they were coming into shallow water, little ripples to the starboard side. A house sat on that side, between trees and inlets of floodwater. Heaps of flood-borne brush were banked along the highwater mark, and what land was not flooded was pitted with small lakes permanent enough to grow reeds in profusion.

"See that place?" Amos asked.

"Looks like that farm is lost."

"You set foot out there and you'd go in up to your knees even where it looks solid. Can't work it any more, no way. Only survival crops will grow there now, and that just summertime vegetables. Nothing much. The river used to keep its banks here and this was a beautiful farm. There were levees and a house nearer the river when I was a boy. They lost two children when the first house went. Rebuilt then. The old man lost his wife in the flood this spring. Now he sits in that house with the windows all out and not enough to eat and takes shots at anyone that comes onto his land. He may be dead now. I passed this way by night and didn't see a light. So he's likely gone, or out of lights. Same with this whole forsaken riverside. We know the score, but it's our world, and we'll stay in spite of all them that try to make us go. You want to understand Hestia, friend outsider, well, understand that old man. Understand us that lets him stay. We got no use for Earthmen and Earthmen's attitudes. Mother Earth ain't our mother, and I don't know why you come out here, but I'm sure you've found out by now that we haven't got it. We're a little touchy in temper; a lot shy of outsiders' help. But you help us on our terms: that's help. That's help we can do with. Maybe you got the sense to see that. I hope so."

"If I have to build where you say build, I can't guarantee anything; but if that's the way you want it, that's what you'll get. I'll tell you my opinion on it, but I'll do it if that's my only choice."

"You know, there ain't a man or woman on Hestia that don't know they could pack up and ride the next starship out. But no one's done it, not one. We're stubborn. We stay."

"You think you have the resources to stop the river?"

Amos frowned. "Well, about that, I don't know. I seen the river win every round so far. But we just give a little when it does."

Merrill had expected the boat to tie up at some dock to spend the night: it was a good many days' traveling to Burns' Station. But well after dusk she was still running along at a much reduced speed, with nothing in sight but the distant lonely lights of an occasional house on the southside ridge. The slap and suck of water at the moving hull, the monotonous slow sound of the engine, were all alone in the dark. Celestine held the center of the channel, with one dim lamp burning outside the wheelhouse.

At last, while Amos took the wheel again after a long rest, Jim opened up the only cabin space Celestine had, a low-ceilinged and poorly ventilated hole under the wheel-house, into which it was only possible to crawl. Jim went first; Merritt followed, found thin mattresses and a nest of sheets, cushioning from the bare planking. A little light found its way through louvers, and a cold wind relieved the stifling warmth; but the engine made a deafening racket and sent a vibration through the very planking of the deck, making sleep doubtful.

"It's the best we got, Mr. Merritt," said Jim. "I know you're used to better, but that deck gets cold before morning. There's more comfort here."

Merritt worked his way to the center of one pallet, and fought the sheet and blanket into order in the dark. The sweat began to run on his face. He rolled onto one arm in the narrow space and began to work himself out of the jacket and boots, with the slow chug of the engine jarring his bones. "Do you go at this by shifts, you and your father?"

"Yes, sir. At least on this stretch, where there's no safe dock to tie up to. Can't run a cable to shore just anywhere, 'less you're willing to take on all sorts of pests. That's why Dad and me do most of our sleeping by daylight. Safer that way."

Merritt turned on the pallet, drawing a single sheet up against the roughness of the blanket. "I guess there might be something in it. I don't seem to appreciate just what you do have to contend with—or a lot else on Hestia, for that matter."

"It must be something—to travel aboard one of the star-ships."

Merritt frowned at the unexpectedly wistful tone, regarded the boy curiously in the barred light from the louvers. "I didn't think Hestians entertained such ideas," he said, and almost before the last word had left his mouth he guessed he should not have said it.

"Did they tell you that?" the youth asked, suspicion hard in his voice.

"What?"

"That I'm half offworlder? Or does it stand out that bad?"

"No, no one mentioned it. I didn't know it."

The boy sank back, bars of light rippling over face and arm and into dark. "No matter, then. Forget it."

"Do you ever think of taking one of those shuttles off Hestia?" Merritt asked.

"No." And a moment later: "That's a lie. But I got too much here and too little elsewhere. There's a lot of downriver Hestians that have my kind of beginning; and they just stay downriver Hestians—which ain't much, if you know Hestia. New Hope's a sinkhole. But this old river— he's something else. This is Hestia. You don't know us til you know the upper valley. And that's the thing the star-ships have never touched. —Yes, I've thought of leaving. I've thought of it every year I watch one of those big silver ships go up out of sight. But I got no idea what they go to, and I know that the Millers and the Burnses and so on are waiting for Celestine. So we're back upriver again."

Burns' Station hove up against a cloud-rimmed sky, sun-stained wisps of fleece against black, bristling bills, and the station itself less farm than hill-fort, house and girdling walls and outstructures of stone set high on a promontory where the river bent. The facing height was dark with woods, but the trees were cleared back at a considerable distance on the occupied side, providing a measure of farmland and pasturage.

Dusk was settling thick by the time Celestine chugged in to the floating dock. Two blasts of the whistle brought a stir of life from the hill, gates opening, lantern-bearing men hastening down the face of the promontory on wooden steps.

There was no lack of hands to receive the cables: Jim hurled one coil from the bow and Merritt cast the second from the stern, hastened to help Jim run out the plank, while the engine fell away into silence and Amos joined them at the gangway.

Hands reached to steady them, friendly faces lantern-lit, all male and most bearded. Jim went first and shook hands and pounded shoulders; Merritt followed into the commotion, ignored for Amos, who came after. "Engineer," Amos said of him, and there was a cheer and no scarcity of hands held out in welcome.

"My equipment," Merritt protested as the lantern-bearers began to climb; but some men stayed and began to unload for them, and he let himself be guided up the wandering board steps, up and up to the station's open gates.

Another group waited inside them, in the dirt yard, where there was a blaze of torches, where slits of windows in the stone house showed yellow of firelight, and big square windows on the upper floors blazed friendlier welcome.

A great red-haired fellow came out from the rest to Amos and grasped his offered hand in friendly violence, then looked at Merritt, face frozen in a remnant of a smile.

"Frank," said Amos, "meet Sam Merritt. We got ourselves an Earthman engineer. —Sam, this here's Frank Burns. The Burns, head of station."

Burns grinned pleasantly and thrust his big hand toward Merritt. "So they heard us. But—" he asked suddenly, looking beyond them to the others, "wasn't there supposed to be more of you? You got no crew, no helpers?"

"I'm afraid not," said Merritt

"Wait a minute now," said a balding man to Burns' left. "Earth promised us at least two men and a work crew."

"I'm sorry," said Merritt. "I'm all you've got."

There was an angry murmuring from some present, that made Merritt suddenly doubt his welcome and his safety, but Burns set a heavy hand on his shoulder and looked at the man who had objected.

"Mr. Merritt," Burns said, "want you to meet Tom Porter. Tom's a neighbor of ours, come up to wait out what Celestine'd bring us. Tom Porter's holding's big as ours and right next, lots of families in Porter's Station, but they use our landing."

"Mr. Porter." Merritt accepted the offered hand.

"Glad to meet you," Porter said, belated grace. "Fact is, we're glad to get any help at all, but we'd hoped for more."

"I wish I had help too," Merritt said. "But I'm told you can supply manpower and some supplies; we've precious little of the latter."

"We'll manage," said Burns. "Hey, I don't know what we're standing out here in the wind for. Ken, Fred, you boys set what gear there is in the shed, and baggage in the main room, anywhere you like. —You timed it right Amos; Hannah's just got dinner on the table."

"Good," Amos grinned. "Been looking forward to a winter with Hannah's cooking. How's things here?"

"All right. Mostly all right." Frank Burns hailed them into the open doorway of the big main house, into light and warmth; and behind them the outer gates creaked shut and most of the crowd followed.

It was a grander house, in its stone and bare-beams style, than the governor's mansion in New Hope; and it was newer. The floors were split planking, massively solid; the walls were hung with necessities, rope and other such items; the furniture was hand-hewn and use-smoothed, and the air smelled of woodsmoke and savory food. Oil lamps and an enormous fireplace gave light, cast shadows back into retreating hallways and to a balconied upstairs. Women and children hastened this way and that setting the table; an ignored baby screamed indignation. Outside, cattle lowed and sheep bleated; and inside, human voices shouted over the confusion.

"We're hotel as well as farm," said Burns. "The last place on the river, the highest ground in flood: half a dozen farms round about do their meetings here and their trading at our dock, and come here when it floods. Same with Tom's place downriver. How long do you figure to stay over, Amos? Did I hear you say all winter?"

"Don't really know," Amos answered. "I'm supposed to stay by our friend here and provide him the use of a boat when needed…" He paused to grin at some elderly acquaintance and to shake hands and exchange words briefly. There were the center of all the gathering now, old and young clustered about them, the children dancing about and asking for some treat brought from downriver. It was impossible to talk at length. "Give it up," Burns said when Amos tried further. "Shed the coats and sit."

Merritt unzipped the jacket and surrendered it to a child who held out her hands for it, turned tableward and let himself be placed near the head of the long board, next Burns himself and Amos and Porter, and Jim on the other side. An older woman came up drying her hands on an apron and offered her own welcome. "Hannah Burns," she said of herself, the while a boy shouldered in at Merrill's other side to put down a cup of tea, and food was appearing in huge bowls and kettles, seized and passed one to the next with great care.

"A pleasure, Hannah Burns," Merritt said. "Sam Merritt. Thank you for making room for us."

Hannah Burns gave a short nod and something caught her quick eye: she shouted a name and instructions about serving and was off again. Merritt blinked, noting the unbroken line of male faces at table: neither women nor children. All at once there was the feeling of difference, his own manners, his machine-woven clothes and smooth-shaven face an alien distinction.

"How soon," asked Porter, leaning forward with a spoon in hand, "how soon you going to get started, Mr. Engineer?"

Merritt paused to let the girl making the rounds with the kettle of stew ladle some past his shoulder to his plate, thanked her with a nod and leaned forward again. "Well, as soon as I can. It'll take me some little time to look over the possible sites—"

"We did the looking," Porter shot back. "We don't have the time for you to take five years at this project, Mr. Merritt. We got families down there in the lower valley that are going to be washed out next spring, that are praying now the floods don't get worse before winter stops them. We need help now, quick. We got no time to wait."

Of a sudden the table chatter had fallen away. The bustle of women and children faded. The whole room was listening. Only the barking of a dog sounded outside.

"If what we build doesn't hold," said Merritt, "I don't need to tell you what will happen next spring. That would be a disaster, Mr. Porter."

"I think," said Burns from the head of the table, "the site we have in mind is a good one. It's just half a mile upriver from here, where the canyon narrows the river down. There's a good deal of rock there to be used, and the canyon splits the upper valley basin from the lower. We can't get men or supplies any farther into the Upriver, and building the dam downriver would wipe out the best farmland we've got."

"It sounds reasonable," said Merritt. "But I'll still have to see the place myself before I can start making any plans. I'm aiming at a spring deadline too, Mr. Porter. I saw enough of what you're talking about on the way up the river that I very much understand what you mean. But I don't want to waste our limited supplies or risk lives and property by jumping into this without study. I can promise you I'm going to be working steadily from now on, and by the time the water falls so that we can start working, I hope to have some plans drawn up. You can help now by finding a crew to work."

"Burns and I can raise a thousand in a month," said Porter. "Do you need more than that?"

It was a fifth the total population of Hestia. Merritt considered the two of them, one side and the other. "What we'll need depends on the time and the site and the amount of rock we'll have to move."

"You'll have all the help we can give," Burns assured him. "You understand, Mr. Merritt—we've seen a lot of land and no few of our friends and relatives lost to that river. It doesn't get easier to be patient, knowing we're within sight of an answer. I can't tell you how anxious we all are to see this project underway, but we understand the difficulty involved. We've tried it twice ourselves and lost."

"Well, I'll get out to that site of yours first thing tomorrow and see what I can learn."

Burns made a deprecating gesture. "No, no, Mr. Merritt. Take a day to catch your breath; I'm hurrying no guest out into the edge of Upriver. I've got some charts of our own may interest you, and lists of the supplies we've been storing toward this project for years."

"Frank," said Hannah Burns, coming to lean on the man's chair-back, "I'm sure those things can wait til late tomorrow. Let 'em eat in peace, for pity's sake. I'm sure they're tired." She lifted her eyes to Merritt, smiled tautly with a crinkling of sun-wrinkles. "Room's waiting on you. Good meal and steady land underfoot and you'll be wanting it. Trust it more than old river: good walls and lots of folk around you. You'll sleep here, no worry."

After cramped, sweltering nights and cold days on Celestine, the little room upstairs in Burns' house was luxury: quaint, with the same rough furniture and handmade rugs and a pillow-soft bed. Merritt tested it fully clothed, lay back in it with the billowing mattress rising about him and shut his eyes a moment, opened them again to watch yellow lamplight flickering on dusty beams. Adam Jones seemed incredible from such a perspective.

A wood stove gave heat, too much heat, and the room was close. Merritt rolled out of the yielding mattress and went to the shuttered window, unbarred and opened it, inhaling the clean, free wind out of the dark… leaned there, looking out. There was a view of a slanting, shingled roof, and after a little gap, the roof of a shed, and an irregular portion of the yard, then the stone wall and the forest. A torch gleamed, moved, vanished. The yard, the whole house was settling for the night. The noise downstairs had sunk away.

He turned away, opened the luggage that one of Burns' folk had set beside the door and began to unpack, considered the task of arranging his belongings for a moment and gave it up, hung out only what he meant to wear on the morrow, and set his shaving kit on the table.

Someone came up the hall—traffic came and went with the house arranging itself for the night; but the steps stopped and someone knocked.

"Come in," he said, half-turned, and found a young woman there, her arms full of towels. Her first glance was to him, the second to the open window, and she deposited the towels on the bed and went at once to the window, closed it and the shutters, fastening them with the bar.

"I'm sorry," she said. 'That's awfully dangerous, to sleep that way. We keep the windows shuttered at night and the doors bolted."

"Thank you," he said, taken aback.

"Meg Burns," she said, smiling suddenly. "Daughter."

He had seen her downstairs, but the lights had been poor. Standing next the lamp as she was, her red-brown hair acquired a brightness, her brown eyes a gentleness that stopped one for an extra glance. No competition for Adam Jones' light-of-love daughters, perhaps, but there was a healthiness about her that had its proper place in wind and sun, not a starship's sterile atmosphere.

"I brought the towels," she said. "There's a bath down the hall at the end and hot water on the stove there; you refill it for the next and don't dump the tub til has to be. And I'm sorry about the window, but the light draws all kinds of pests.—If you wake up for breakfast in the morning it's ready at daybreak. Just come downstairs. There's always enough. Or sleep over. That's no matter either."

"Thank you," he murmured a second time, and Meg Burns turned to go, smiled at him over her shoulder as he smiled at her, then was off down the hall outside with a patter of slippered feet.

He closed the door after, considered the closed window and put the towels on the table, looked again to the door.

Not the manners he had known, he decided, reckoning the way of things at table, the implications in the house of order of a different sort than he easily guessed: caution settled on him, a conviction that there were borders and barriers here.

He tried the bath, in line after one of the Burnses: the way was to learn who was next and knock on that door when finished. The bare-boards room was stiflingly hot and humid, and there was no plumbing but a drain in the floor and an admonition posted to empty only washwater down.

And in the morning, with a pain in his muscles from the too-soft mattress, he considered his outworlder clothes and his outworlder manners and still shaved, still dressed as he would have aboard the Adam Jones. He had his own ways, and purposed to keep them.

Daylight put a bright complexion on the fortress-station and on all the land about it. His belly full of a fine breakfast (he had been late, but Hannah Burns had saved eggs and sausage for him, a special case among her guests), Merritt climbed the grassy slope to the crest of the promontory over the river, his hands jammed in the pockets of his jacket, for there was a chill in the morning wind, more than he had known on the river.

The clouds were entirely gone, leaving a sky of brilliant blue, a pale morning sun too small for the sky, a landscape of unsuspected colors sprawling out in the first clear daylight he had seen on Hestia: oranges and yellows and bluegreens of autumn in this alien woods, with no rain to curtain them.

At the base of the promontory the river ran rough from the narrows, yellow-brown with silt. Celestine bobbed at her moorings at the dock that was sheltered by the bending of the river, toy boat on a river gone miniature. A sound of water came up the deep, a trick of the air currents.

Against the northern and eastern sky rose more mountains than he had yet seen, a bristling outline usually hidden by the rains: foothills of the Divide, source of floods and barrier that made the weather. It was the Upriver, at least part of it, its nearer approaches mantled in dark forest.

The wind grew bitter. Merritt turned his shoulder to it and pulled his hood up, glanced back at the station's rambling walls, at the fields and the meadow downslope. Two of the women sat with the sheep, while a black dog and a brown one trotted the limits of the flock.

It was a way to walk, a lee side out of the wind: Merritt made a slow and casual descent, and when he had come nearer the herders and the sheep, he recognized one of the two shepherdesses in coveralls for Meg Burns.

She saw him at a distance and waved a hand in tentative greeting. He ventured out across the dew-wet grass, walking carefully among the skittish sheep, causing work for the dogs, who worked them back together.

"Good morning," he said to the women, and both, seated on a bare space of rock, gave him polite nods of welcome. Meg stood up then, regarded him in her own way as warily as did the brown dog who came to sit at her side.

"Making up your mind where you're going to build?" she asked him.

"I've been looking at the charts and thinking on it." He gave a perfunctory smile at the half-grown girl who was Meg's companion, looked back to Meg. "Do you know the river beyond this point?”

"Not well," she said. "I don't go there. No one does."

"Have you lived here all your life?"

"I was born here," she said, and smiled in a way that made her ordinary face beautiful. "I'm afraid we're not travelers. I've never been anywhere at all."

"What, not even to New Hope?"

"No," she said, "not even to the next farm."

"Don't you sometimes worry about living right here on the edge of the human world?"

She laughed silently, as though the question surprised her. "Not really. Not often. Our place has always been safe, our walls keep us that way, and most of the things in the forest are afraid of the dogs. We're all right if we come away from the forest before dark and never take the big trees. We're agreeable to it and it doesn't bother us; that's how we live here. We fit in."

Things might change when the river changes, you know."

"I know. But that has to be, after all. Everything will change. But then maybe Hestia will be somewhere worthwhile. Maybe Earth will send us more help then." She looked out over her flock, whistled and pointed, and the dogs ran, headed off a stray from the edge. She turned then, looked back at him. "I've grown up here," she said. "And for most of my life we've been waiting for you. I'd almost given up."

To that, he did not precisely know what to say. It was, in all, a better argument than the governor had used.

"Do you think," he asked, "that you could show me the place your father thinks we ought to build? Is it too far?"

She looked a little doubtful, looked into his face as if she were estimating him. "All right," she agreed after a moment. "But you'd better go back to the house after a gun."

"This is it," said Meg Burns, balancing surefootedly on a pinnacle of rock. The dog scurried about the brush in the forest behind them and started nothing but birds.

Merritt looked down where the water boiled white far beneath them, and up to the valley which had been invisible from the point at Burns' Station.

The crest on which the station stood and this narrows where they now were formed a natural barrier between two great valleys. A dam was indeed possible here, at least by first sight. The eastern valley would be destroyed, almost totally inundated up to the steep slopes of its wooded mountains, but men on Hestia had a great deal of land from which to choose. Now it was a glory of autumn colors, of rock spires and tall conifers.

"It's a shame to do it," he said, looking about him, "but I suppose there's not much other choice, even granted we could get a boat up past that narrows…"

"There's rocks," said Meg. "We had an accident back a few years ago when we were trying to build on our own: one of the boats hit a rock and blew up. The boiler exploded and everyone aboard was killed. Twenty people. I don't think you could ever talk Amos into going up to the edge of that. Besides, the high valley is full of troubles. It's not a pleasant kind of place at all, and you wouldn't get men to carry supplies across it.”

"It's some country, all right." Merritt cast a look eastward, where the tops of trees lay like a mottled carpet as far as the mountain-skirts, a bluegreen and orange expanse cut by the veinwork of streams and the river itself. There came no sound but the distant rush of water and the wind sighing through the leaves… the occasional rustle of the brown dog which accompanied them and coursed off on her own business in the thickets.

"Lonely," said Meg after a moment "Is it like Earth? Is it anything the same?"

It struck him with an eerie feeling, that this Hestian would have to ask: a century removed from the mother-world, they had all a slightly separate accent and named with earthly names things which were only superficially like their earthly counterparts—having forgotten, perhaps, the original. The colonial program had birthed something it perhaps had not planned: a generation of men who had no understanding of Earth.

"It's like," he said, '"or it used to be. There's little wild land left there now."

She looked at him with the hint of a frown. "You must think we're very backward."

"I've no complaints."

"Why would you have come out here?"

The governor persuaded me."

"But why all this way to Hestia in the first place? It's a long way to come, for the sake of strangers."

"Well, my reasons seven years ago were different from those that got me upriver, and maybe after a little while my reasons will change again."

She gave him a sideward glance, settled on a faint smile. The light red-brown of her hair and the flush of her cheeks and the slight freckling from the sun were the colors of Hestia itself. He had not thought her strikingly beautiful when he first saw her: it was like something he had privately discovered, in the sun and the slight crinkling of a smile. He wondered her age: nineteen, twenty, perhaps; and whether she knew what effect she had on a lonely man.

"We ought to get back," she said, suddenly breaking away from his eyes, and clapped her hands to call the dog. "My dad will worry if we're gone out here too long. They'll be sending searchers out."

"You don't take walks much, I take it."

"No, oh, no," she said, and bent to clear a branch. "We're still within reach of home right now, but just at the foot of the rocks down there, that's where the Upriver starts. That's the end of it. That's the line we never cross."

The sleeping house was quiet, no light showing under the crack of the door. Merritt lay stone-still a moment, at last lifted his head from the pillow, plagued by the indefinable sensation of having heard or felt something. There were noises, but only the expected ones, boards giving with the weather, the sighing of wind at the window, something that went bump in time with the gusts.

A dog barked, suddenly, hysterically; and sheep and cattle outside surged against their pens, bleating and bawling in wild panic. Steps crossed downstairs at a run and someone took a clapper to a metal pan and started beating on it. It rang like doomsday and Merritt came out of bed wide awake now, scrambling for his clothes and his boots and his gun.

He reached the balcony of the main room armed and half dressed at the same instant as Porter and Meg and some of he other residents. Merritt followed them, scrambling downstairs with others coming behind and more assembling out of the downstairs wings, men and women in night-dress scurrying about checking bolts and bars.

"Hey!" someone yelled at Merritt. "You got your window closed and bolted?"

"Yes," he called back.

"One of you girls double-check those upstairs windows in the hall," Burns shouted. "Hey, Amos—where do you think you're going?"

Amos Selby was struggling into his coat, and Jim likewise, already heading for the door. "I got my ship down there," Amos said, "and I got too much at stake with it to sit up here."

Jim was with his father as he unbarred the main door and ran; and Merritt hesitated in confusion what the threat might be. But he was certain that he had in his own modern gun a far more effective weapon than the two Hestians carried, and that Amos and Jim were doing something rash. He snatched someone's coat from the peg and ran out after them into the dark yard, trying to overtake them both before they could leave the security of the walls. Someone behind them was cursing all of them and ordering him to stop, whether from anger at the coat or from fear; he heard men running after them.

Amos reached the main gate and hauled up the securing bar, let himself and Jim through to the outside, and it was there that Merritt overtook them and the Porters caught up with all of them from behind. There was a view of the river from the gate, with the steps lacing back and forth down the steep face of the hill; and the first thing evident was that Celestine was free of her cables and headed downcurrent sideways.

Amos cursed under his breath and started running—old man that he was, he could run; and headed off the slanting side of the promontory across the grassy descent toward the trees and the bending of the river.

Merritt saw what he was trying to do, in overtaking Celestine; but the course was going to take them through brushy areas and past a dozen opportunities for ambush, and the current was faster than they could possibly run.

Jim came in at a tangent and skidded downslope, cutting ahead by a little, lost for the moment in brush.

"It's no good," Merritt yelled after them in despair. "Give her up. It's no good killing yourself."

Amos paid him no heed, ran stumbling onward until he could go no farther and pulled up holding his chest; but Jim kept going.

"You got a gun," Amos gasped when Merritt stopped for him. "You stay with my boy. He hasn't"

Merritt hurled himself off then, trying to overtake Jim; Porter was close with him, though some of the others had stopped for Amos. Jim stayed ahead, a Sitting shadow in the brush, refusing their cries to stop.

The river broke sharply to the left just ahead: and Celestine had stopped. They came on her aground on a bar, her dark bulk discernible against the moonlit water.

Jim stopped among the saplings on the shore; Merritt overtook him, and so did Porter and his men. "She's not bad," Jim said, and began stripping out of his coat "I'll get out to her."

"Hold it, boy," Porter said. "No telling what you might meet aboard."

"Somebody's got to get out to her," said Jim. "I'll make it all right, and the People never yet went around machinery. I'll start her up and see if I can't work her off that bar."

"You be careful, boy," Porter said.

"Yes, sir." Jim handed Merrill his coat; and Merrill tried to shape some objection, but none would organize itself: he knew the rivermen too well. It was their life and livelihood sitting out there; and it belonged lo Amos, and Jim, half a son, could not lose it.

A slender figure in the moonlight, Jim stepped down to water's edge and tried the temperature of it, bent over a few moments to get his wind before attempting it. Then he stepped off into the black waters and went in up to his waist.

Gingerly he waded out, not yet having to swim. Once, twice, the dark spot in the water that was Jim's head went out of sight, then reappeared; he was swimming now, fighting the current

Amos joined them, helped along through the brush by one of Porter's kin, and shook his way free to come down to the bank to watch.

"Jim'll get her," said Porter softly. "Don't worry, Amos. We got her now."

"You think I worry about her more than for my boy?" Amos returned shortly, and then kept quiet and watched, for Jim had reached the boat and disappeared into the shadow. There was a murmur of anxiety on the bank. Then Jim reappeared, clambering up the cable by the stern; and there was a general exhaling of breath among the group on the shore.

Time passed. There was no sound from the boat. No one spoke or cracked a twig.

"I'll get her started," Jim's voice called back suddenly. "But I'm afraid it may not be enough to get her off. She's riding too steady to be much adrift."

"You be careful out there, boy," Amos shouted. "Are you alone on that boat?"

"Yes, sir, far as I can tell, I am. Don't worry. If need be, I can ride her out til dawn and we can get some men out here. If she breaks free again, so much the better. I think her bottom's sound."

"Did she break or was she cut?" Porter called out

"She was cut," Jim replied.

The engine started, but it was as Jim feared. She could not quite drag herself free. Cable had to be carried ashore and back again, and it was well after dawn before Celestine could finally winch herself off the bar and into clear water.

It was cold, killing work. At last, with Celestine freed and chugging her deliberate way back upriver to the dock, the crew on the bank started back for the station uphill, blind with exhaustion and half-frozen. There was talk of nothing but dry clothes and breakfast and sleep, in that order, and Merritt flexed skin-stripped palms and agreed with them; there was no feeling in his feet and more than enough in his back, but it was salve to his aches when one of the Porters clapped him on the shoulder and allowed that he was due a drink when they all caught their breath.

They were staggering when they reached the crest, where Burns and his folk held the open gate.

"We just about lost her," Porter said to Burns, when they reached that security, and looked down the height, where the boat was slowly putting in to dock.

Burns gave a long breath, a jerk of his head to the way below. "Earthman—you come down to the dockside. There's something I want to show you."

Merritt opened his mouth to protest, indignant at being turned from the gate. He was too tired even to contemplate climbing steps down and up again; but having won the boat back and being one with these folk set him in a biddable mood .-. . and it was too late: Burns was on his way without pausing for his opinions.

He followed, on numb feet and shuddering knees. At the bottom of the steps Burns waited for him to catch his breath, and waited for him again a short distance farther, off the boards and where the clay of the bank was soft with moisture.

"There," Burns said, pointing down. "There. Have a look, friend, and learn what we've been talking about when we say we don't go into the Upriver. Many a one I've seen, but none quite so clear and plain."

Printed deep in the rain-soft clay, as one would lean against that bank to catch balance in descending, was the print of a long-fingered hand, a hand with an opposable thumb, but with bones too elongate to belong to man or woman or child. A few yards below, at the end of a sliding mark, was a footprint of the same proportions as the hand and toed like a man's.

The prints continued downslope toward the floating dock, where severed ropes were still looped about the moorings, and a handful of Burnses were ready to receive cable from Celestine.

It was one of those blue-ceilinged days that were growing increasingly frequent with the coming of winter. The trees were either bare now, or held the last few leaves, stark skeletons of white among the blue-green shadow of conifers, and the land had gone all brown and yellow, the woods thickly blanketed with leaves that rustled dustily dry.

Notebook in hand, Merritt took the lower trail down to the river's edge around the bending of the promontory. The river was now far lower than it had been at his arrival. Rocks once submerged now stood well above the waterline, and there was a safe ledge to use in skirting the water. It would be possible to get a line across to the other side, with Celestine's help and a little effort on the part of the men; and from that line a footbridge could be begun, to span the gorge. It was going to be necessary to do a great deal of traveling from one side of the site to the other.

He descended to the very edge of the water, walking carefully because of the slickness of the rocks, where white froth curled up to the soles of his boots. And in his mind, gazing at the narrows, he saw the structure that was going to take shape across the throat of that chasm; and the vast lake it was going to make behind it: spillways to let the overflow go, water for fields in season, safety for downriver, the river tamed to the service of man.

Once the river kept its banks, once there was dry and dependable land, Hestia could start to grow. Boats could move at will on the lower course, and even ply the lake in safety; crops would come up in abundance, rail and river transport could move them, making fall use of the steam engine that was Hestia's chief source of power now. Electricity would follow, water-given and solar, and humans live in light and warmth. And beyond that, the world would make itself a respectable colony, a mote of an oasis in the course of starships: all if they could make this one beginning.

All if they had time.

A rustling disturbed the leaves farther up the trail. Nails clicked on stone. Merritt whipped his pistol out and turned, heart pounding, until he saw only brown Lady, tail wagging merrily, come panting up to him. He put the gun away and caressed the dog's silky head.

"Well," he said to the dog, "where's your mistress, eh?"

And a moment more brought Meg Burns down the trail, following Lady.

"Hello," said Meg, dropping down to the ledge on which he stood.

"Don't make up to me," he said. "Didn't I tell you I don't like your coming out to this place alone? You used to have good sense."

She grinned and came into his arms, a pleasant bundle of soft leather and furs and homespun, for the air was cold. He kissed her on the lips and set her back again.

"That dog isn't much protection to you, you know," he told her. "She's not very fierce."

"You don't have anyone at all out here with you. And you stay out so late, all alone."

"I'm armed; you're not."

"That's all right. I don't like guns, and Lady's my ears. —What have you decided out here all by yourself? Why did you send the men back?"

"Because there was nothing more for them to do here today, and I'm trying to make up my mind what to do next."

"What is that, then?"

He sat down on a rounded rock and made room for her close beside him, put his arm about her. "Well," he said, "you know what Porter's sentiments are. He wants that dam built by this spring. And I'm not so sure. I have some thoughts we could do a makeshift job this year, yes, but it's going to rush us. A little more planning, a little more certainty—but you see, if we don't get started right now, there's a good chance we won't beat the spring rains. Porter's been breathing down my neck these last two weeks— had one of his men on the site today that was driving me to the bitter edge. The fellow won't understand what I tell him. He sees it's possible; I see it's dangerous. What do you think, Meg? Do we take the gamble or can we wait?"

"Why ask me? What can I know?"

"Where it concerns Hestia, a lot more than I do. Can the valley survive another year? All I know is what the river's likely to do, nothing more. Is Porter right and am I wrong in wanting to wait, in wanting to catch it at summer low and wait a few months?"

She looked down into the water, unwilling to speak for a moment. "Sam," she said, "it's really chancy, isn't it?"

"It's chancy. And if they want me to gamble everything, lives, property, all the supplies hoarded for this project over years of waiting—it's not like I'm delaying for my own advantage. They've promised me I can be free of my contract whenever I get a dam finished."

There was a sudden tension in her; he felt it. She looked up at him, brown eyes hurt.

"Meg, I don't want to do things that way. I have a few interests here. Personal interests." He drew a smile from her with that, and her arms went about him.

It was quiet there with the river murmuring below them, drowning even forest sounds; and very lonely, only old Lady lying there watching them. He gathered Meg closer and she snuggled against him, warm and soft and content, leaving him to think thoughts that he had put off time and again.

"Neither of us," he said finally, "has any good sense being out here."

"There's no being alone up at the house. Since those men started arriving, there's always someone underfoot."

"Haven't you been told better than to stay too close to offworlders?"

"Yes," she said, a warm breath against his neck, "but you're not leaving, Sam. You'd better not."